Netflix’s Dark is quintessentially German. Set in an imaginary German town Winden, Dark explores the existential implications of time travelling. A strange cave hides in the soaked forest near Winden, the village that hosts a nuclear power plant since Chernobyl. The central conspiracy is two-fold: one is the concealment of time travel and abduction of young children every thirty-three years, and the other is the intricate family relationships, stuffed with lies, murder and betrayal.

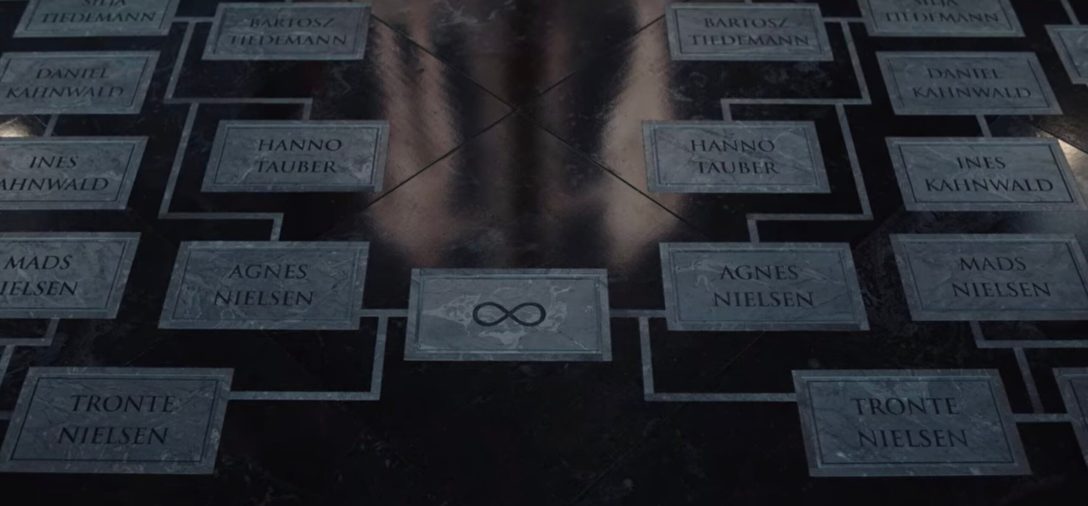

The intricate yet meticulously plotted story spans over two centuries, four generations, three family names (about twenty major characters) and three parallel worlds – all cramped into twenty-five hours. I had to constantly look for the complete family tree online when it became impossible to recollect character relationships. Rooted in modern German thoughts, the philosophical drama quotes, sometimes excessively, Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche, Albert Einstein and Martin Heidegger, the Germans who have shaped the modern understanding of reality, that reality is not necessarily deterministic, and how human will constitutes the phenomenal world apart from the inscrutable nominal reality.

Started as Germany’s Stranger Things, Netflix’s Dark proved to be much more ambitious than its American counterpart. It is also more patient, perhaps: instead of endlessly pumping adrenaline, Dark is a measured, prudent reflection on the circularity of life and the confinement of will. The show just concluded its final episode last year, on a bittersweet note with unsettled feelings, after just three seasons. The mentally exhaustive series prioritises thematic sophistication at the expense of character development. It is understandable, perhaps, as long as the intrusive voice-over does not overwhelm. What it has achieved is a rather philosophical quest, not so much a dramatic production, although no one can deny the production value of its acting, soundtrack and cinematography. The series summaries the summit of German idealism from Kant to Heidegger and asks enduring questions pertaining to one’s existence, fate and purpose.

There are so many philosophical themes and debates to be extracted from the monumental TV series, for instance the fatalist evolution of the self, the perception of time and morality and the Nietzschean will to power. But in this short review, I focus on the concept of causality and how it is associated with time and God. Inspired by modern scientific achievement, Dark is a relentless depiction of human actions on a cosmic scale. It constantly asks the question that, given modern secularity and scientific advancement, has God been denied, or it has evolved? Is modernity as liberating as it is depressing? What is salvation, if it still exists?

Perhaps the most established sceptic in western philosophy, David Hume once problematises our belief on causality. For instance, one only sees the lightening and hears the thundering that follows, but people psychologically incline to supplement the element of causality to the natural phenomenon. That is, people believe that the lightening causes the thundering. Hume radically challenges the idea of causality because human beings cannot witness the onset of causality but only imagine it. What if there is no causality, but only temporal succession? Are humans making horrendous mistakes as they supplement the idea of causality?

Many influential modern philosophical thoughts can be traced back to Hume, and Dark is not an exception. Let us start there, on the difference between temporal succession and causality. The conventional conception of time is linear, and intuitively so. Time only moves forward; the past cannot be altered, and the future cannot be experienced before it actually arrives. Time appears to move at a monotone pace, that is, my time moves at the same pace as anybody else’s time on earth. That is the Newtonian universe, the deterministic, dualist paradise people once fantasise. But reality is much more complex, and the paradigm shift to relativist science introduces a probabilistic universe, a superposition of realities. We now know that time passes at different speeds for different people (moving at different velocities), and physical laws are suspended at the centre of a black hole, a perplexing but necessary consequence of the universe.

While quantum and relativistic physics was not available during Hume’s time, Humean scepticism has become more urgent ever since. Causality is associated with temporal succession, but what if time is a circular formation, the beginning is also the end? What if I give birth to my daughter who will later be transported to the past and give birth to me? What if my teenager daughter grows up and travels back in time to visit me, but I misread her intention and kill my daughter from the future? Who is the cause of this perverse mistake and endless cycle of suffering? Is there an exit from this cycle? There is certainly some tints of Nietzsche’s proposal embedded in this plot, that life is an eternal return, or eternal despair. Is it still meaningful to talk about causality if temporal succession is just an illusion?

A man can do what he wills, but he cannot will what he wills. While Nietzsche affirms one’s will to power, Netflix’s Dark adopts a rather pessimistic standpoint alluding to Schopenhauer. Dark dramatises the illusion of free will, and how life is fatalistic in an endless cycle. Jonas Kahnwald (Louis Hofmann, Andreas Pietschmann and Dietrich Hollinderbäumer) is the reason of his own suffering. He loses his father but soon realises that he was the one who travelled back and encouraged his father to commit suicide. His father is revealed to be the younger brother of his teenage crush: the little boy accidentally travelled back thirty-three years and met his mother. In other words, Jonas falls in love with his biological aunt.

Moreover, his older selves (yes, selves) manipulate him to ensure he will become who they are in the future. Jonas spends his entire life trying to end the cycle once for all, but only to initiate it again and again. He drives the story forward, as the protagonist and the antagonist, running into an endless commencement of shame and pain. At every stage of life, he thinks he knows how to play the game, but only to surrender to his fate. Jonas is a particularly tragic character, perhaps the most tragic I’ve seen in years. He never gets what he wants, and yet he’s the reason why he never gets what he wants. From an innocuous teenage boy with sentimental eyes to a ruthless villain with a deformed face, Jonas never accepts his fate, but only to actualise his fate.

With Jonas, the series alludes to the deterministic evolution of the self, and how the self is both one’s biggest ally and most formidable enemy. The self is an endless loop, a perpetual paradox that cannot be solved as long as one exists in the first place. Jonas is and will always be stuck in the promise and the curse of self-actualisation. Jonas’ older self, Adam, once shares with his younger self –

The God mankind has prayed to for thousands of years, the God that everything is bound with, this God exits as nothing other than time itself. Not a thinking, acting entity, a physical principle with which you can no more negotiate than you could with your own fate. God is time.

Season 2 Episode 5

According to Adam, God, the entity that has been in charge of causality, is no more than time itself. Jonas/Adam spends his entire life trying to destroy time and establish a new world where time will not exist. To correct the quantum entanglement, Adam is willing to sacrifice himself as he should never have existed. The series ends with a bittersweet note. Adam fails to kill himself and correct the entanglement; he does not know how to play the game from the very beginning. The lope must, in the first place, have an entrance, a beginning, as Claudia Tiedemann reminds him. Adam keeps returning to the wrong location, wrong time, only to reaffirm his will and existence.

What is the lesson to be drawn from Dark? I think the show is about the exit, the exit of life’s circularity, the Nietzschean eternal return. Jonas, or Adam, only ceases to exist when he gives up his will. The two worlds, Adam’s universe and Eva’s universe, cannot exist without a third universe, the original universe responsible for the quantum entanglement and the endless loop of suffering. Adam only realises this in the last episode. The way to correct the error seems straightforward – Jonas and Martha (his lover and biological aunt from the second universe) travel to the original universe and prevent a car accident. Without the accident, the watchmaker will not invent the time-travelling machine that accidentally creates the entanglement.

The exit seems deceptively simple, but it requires enormous courage and resignation, given life as the ultimate irony. The exit requires the self to surrender his will and accept the fatality of his choices or his life. Adam cannot create an exit based on his will and rehearse the way out; his will only reaffirms his existence and initiates yet another cycle of suffering. The concluding note of the entire show is not so much tragic as it is therapeutic. Perhaps there is an exit to look forward to – one has always been promised so.