In J.M. Coetzee’s lectures on animal ethics, the moral debate quickly evolves into a metaphysical one. Instead of limiting her discussion to whether it is ethical to kill animals, Elizabeth Costello, the protagonist in Coetzee’s fiction, challenges the status of reason and its moral significance. In Peter Singer’s response to Coetzee’s lectures, Peter, the fictional protagonist, offers an implicit defence of reason. Peter appeals to the practical necessity of reason in moral discourse while remaining indifferent to its metaphysical status. In this essay, I first spell out Costello’s challenge of reason in her lecture. I then consider Singer’s implicit worry about the moral consequences of Costello’s metaphysical proposal. I conclude by commenting on how the fictional form of Singer’s response serves as his ultimate argument and dramatises a debate that is far from settled.

In Costello’s lecture, she spells out her discomfort towards the Cartesian metaphysics and its prioritisation, if not divination, of reason. The emphasis on reason allows not only Descartes but also many contemporary philosophers, to differentiate humans from animals (and machines) as well as to justify the superiority of human consciousness over animal consciousness. However, Costello argues that “reason is neither the being of the universe nor the being of God” (LoA 23). Instead, reason is only one tendency of human thought (LoA 23), and therefore, it is not sufficient as the basis of assuming the superiority of human lives over animal lives. Furthermore, Costello takes a more controversial position and argues that reason is a “vast tautology” because it cannot dethrone itself (LoA 25). Instead of seeing reason as a divine gift, Costello finds it a manifestation of human arrogance and a shaky justification for the superiority of human lives.

Costello, on the other hand, proposes a different metaphysics of being, namely the “full of being”. Instead of prioritising rational thinking over other types of human experiences, Costello sets aside reason as one tendency of human thought while embracing a wider spectrum of human experiences and thoughts such as one’s feelings and embodied instincts or sensations. Costello argues that philosophers need to understand human reasoning more broadly because imagination and empathy can count as different modes of reasoning. Compared to the Cartesian metaphysics of being, Costello acknowledges more modes of reasoning beyond just rationality (Mulhall 38). Similar to Descartes, Costello’s metaphysical commitment has moral consequences. Costello argues that human beings and animal beings are both “full of beings”, and they are equally entitled to the right to life (LoA 33). This is because based on their encounters with animals, people can sympathise with animals and imagine what death would mean for them, and such sympathetic imagination should not have a limit (LoA 35). Relying on sympathetic capacities and imagination, one should realise that animals are equally entitled to the right to life, just like humans.

Singer has an implicit response to Costello regarding whether moral discourse should be based on the “full of being” and unbounded sympathetic imagination. Having written a book advocating that all animals are equal (LoA 86), Peter does not seem willing to push his egalitarianism further to argue that animals and humans are equally entitled to the right to life. That is, Peter thinks that human lives are still more valuable than animal lives. Among various attempts to convince his daughter, Naomi, of his position, Peter argues that if killing animals is painless and unanticipated for them, it would seem justified to kill animals for meat consumption. Naomi, the potential ally of Costello in Singer’s reflection, quickly rebuts that painless killing is only a theoretical set-up that does not represent animal farms in the real world. Ignoring Naomi’s first complaint, Peter even pushes further and argues that he can even replace his pet dog, Max, to meet the demand of dog-breeders so that “there would be just as much of all those good aspects of dog-existence (considering society as a collective whole)” (LoA 88). The response clearly does not satisfy Naomi who complaints that philosophy has carried Peter away, and too much reasoning without feeling has made him cruel (LoA 88).

In the fictional dialogue above, Naomi, standing for Costello, spells out a similar discomfort towards philosophy as an academic discipline. That is, focusing too much on theoretical reasoning without sympathetic imagination, contemporary philosophy seems detached from real life. As a reply to not just Naomi, but possibly also Costello, Peter argues that:

[S]o lay off with the ‘You reason, so you don’t feel’ stuff please. I feel, but I also think about what I feel. When people say we should only feel – and at times Costello comes close to that in her lecture – […] We can’t take our feelings as moral data, immune from rational criticism (LoA 88-89).

Setting the bitter tone and the frustration in this quote aside, Peter argues that to prioritise rational thinking in moral discourse does not mean to overlook feelings (including sympathetic imagination) entirely, or to give up Costello’s “full of being”. In fact, emotions and embodied sensations are part of one’s experiences, and Peter acknowledges that fact. Still, one actively thinks what one feels, and feelings should be inferior to rationality in moral discourse. Committing to the “full of being” and sympathetic imagination, Peter argues, seems non-discriminatory and might make moral discourse infeasible and arbitrary. It is important to note that Peter defends the necessity of reason in moral discourse without invoking another metaphysical discussion. Peter does not divinise reason like Descartes, but he nevertheless thinks that rational thinking should be prioritised in moral discourse due to practical concerns.

It is both surprising and expected that Singer responses to Coetzee in the fictional form. It is surprising because as a renowned analytic philosopher, Singer is expected to “keep truth and fiction clearly separate” (LoA 86) and write in an argumentative style. It is at the same time expected because Singer’s quirky reflection dramatises the debate, and the literary form is itself an argument. Although Singer names the protagonist Peter the philosophy professor, one cannot simply equate Peter, the fictional character, with Peter Singer, the real philosopher. In fact, including characters such as Naomi further complicates the interpretive task. Singer seems to be well aware of potential responses from Costello, framed in the voice of a smart teenage girl. But Singer also cannot equate Costello with Coetzee; the interpretive trouble is mutual. In fact, Singer is very aware of the formal decision he has made, as the fictional character Peter confesses that he does not know how to respond to Costello, and above all, he has never written a fiction. Those ending paragraphs echo Naomi’s très post-moderne (LoA 85) comment at the start. Singer is undoubtedly playing with the self-reference game and blurring the distinction between reality and representation.

The purpose of doing so, I think, is that Singer wants to push the interpretive trouble back to Coetzee while implying his argumentative position with a fictional father-daughter dialogue. I argue that Singer has to write in a fictional form because it serves as the ultimate endorsement of Singer’s moral philosophy based on reason. Singer’s literary reflection does reflect the full of being: it features elements such as familial relations, emotional attachment to personal pets and frustrations about one particular intellectual discourse, elements one normally do not find in a philosophy essay. Just as Peter says, Singer the renowned philosopher also has feelings, and he is not always theoretical. Still, Singer’s literary form creates more interpretive issues and seems to accuse Coetzee of begging the question. Using the story as a whole, Singers seems to argue that one always feels, but one nevertheless needs to think about what one feels because feelings create mutual interpretive trouble and render moral discourse inconclusive. That serves as Singer’s final endorsement of reason. Although Singer does not propose a Cartesian argument regarding the divine status of human reason, he does think that reason is necessary for everyday moral discourse.

To conclude, I would like to return to one of Peter’s comments which quintessentially captures Singer’s response to Coetzee. Peter claims that Costello is “on the right side” (LoA 86) regarding animal ethics, but advocates “a more radical egalitarianism about humans and animals” (LoA 86) that Peter is not entirely comfortable with. What exactly makes Costello too radical for Peter? Although both advocate for some form of egalitarianism, Costello pushes her moral debate further and challenges the metaphysical status of reason. She even proposes an alternative metaphysical basis for moral discourse, namely the “full of being”. Singer finds that move radical and unhelpful for the moral discourse regarding animal ethics. Although Singer does not explicitly endorse the Cartesian metaphysics, he does find reason a practical necessity in everyday moral discourse. I think that Singer’s argument has a more modest goal. As acknowledged by Singer himself through the mouth of Naomi, Peter’s response cannot fully satisfy Costello who has a more ambitious metaphysical argument in mind. The moral and metaphysical debates, which inevitably correlate, are both far from settled.

Works Cited

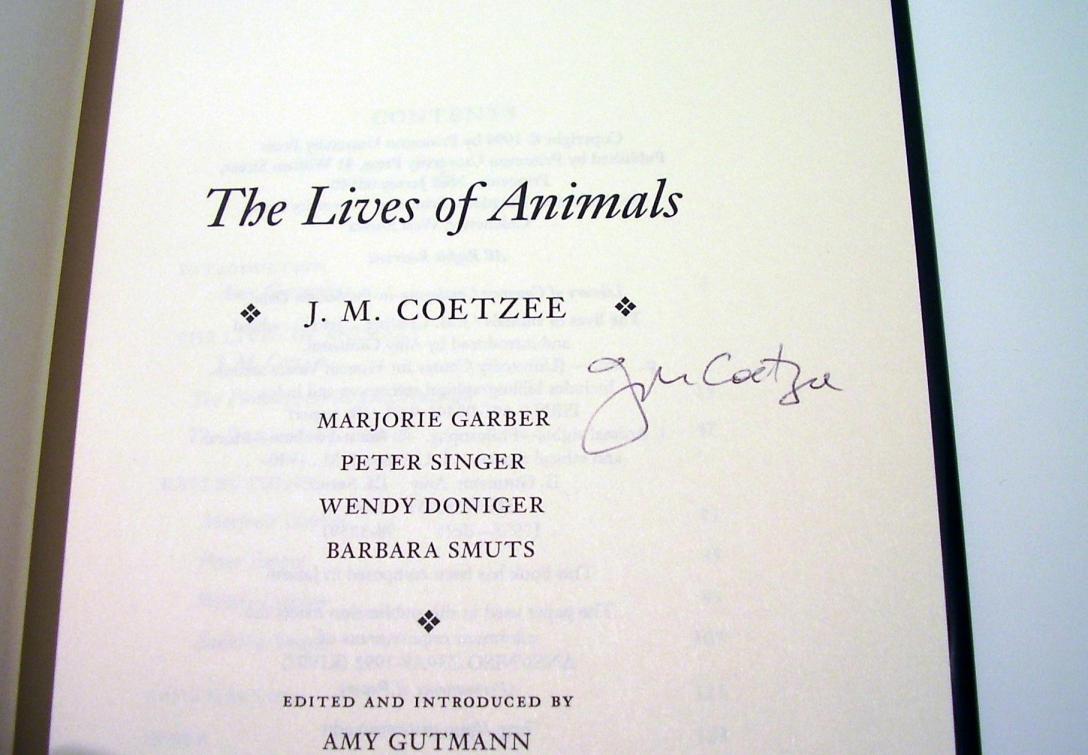

Coetzee, J. M., and Amy Gutmann. The Lives of Animals. Princeton University Press,

Princeton, New Jersey, 1999.

Mulhall, Stephen. The Wounded Animal: J. M. Coetzee and the Difficulty of Reality in

Literature and Philosophy. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2009.