Thoughts on Two Sides of the Same Lens

Paradoxically, documentary as a film genre has often featured camera footage and editing techniques that are derivative from its original dedication to realism. It is almost the inherent dilemma of every documentary maker: she wants to re-present reality as it is, or was, but she can never achieve it given the staged nature of documentation and the living, conscious subjects being documented. In other words, documentary is equally guilty of manipulating reality and privileging certain images, opinions and narratives over others. Still, documentary is often associated with its moral language. The audience of a documentary (rather than, for example, a fictional horror) are more likely to feel compelled to act in a certain way and to ethically respond to a situation. How can one reconcile the implicit manipulation of reality and the strong moral imperative that seem to coexist in a documentary?

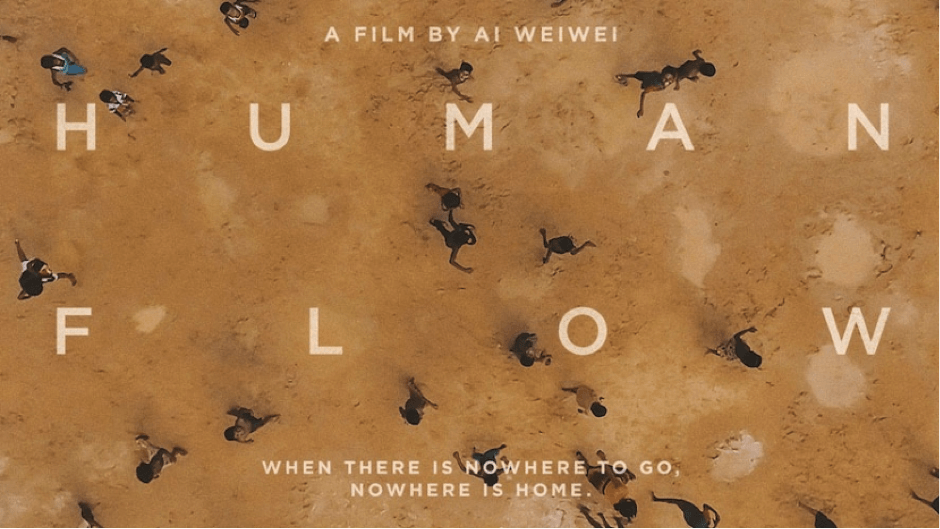

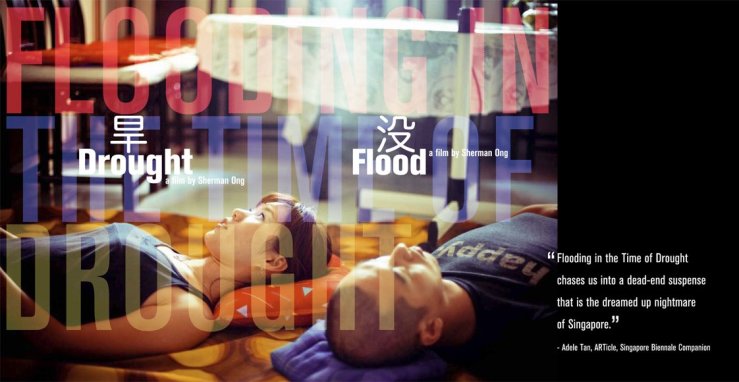

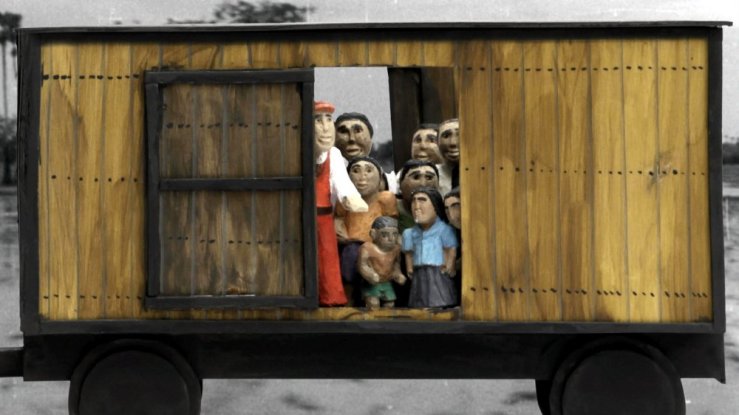

As an attempt to address that question, this essay reviews a film series entitled Two Sides of the Same Lens, organised by the NUS Museum. As part of the museum’s Outreach and Education initiatives, the series consists of five films in conjunction with three exhibitions in the museum: Homeless, Crossings, and Of Place and A Paradox. What thematically unites these films is the suffering, or melancholy, of being forced to leave one’s home, and the underlying moral imperative that compels the audience to reflect on current politics. The documentary dilemma is evident in all of these five films. In Human Flow, for example, the director broke the silence and participated in some of the scenes as a comforting stranger. The daughter in Last Train Home once broke the fourth wall and shouted to the camera. Although inspired by real-life experiences, stories in Flooding in the Time of Drought happened in an imaginary, drought-stricken Singapore. In The Missing Picture, clay figurines are used to reproduce missing historical events and narratives as few visual recordings have survived. None of these films dutifully replicates reality. But that does not disqualify these films as documentaries. Perhaps documentaries are meant to stimulate moral imagination with those subjective, intrusive elements. Perhaps they are ultimately concerned with moral realism instead of visual realism.

“Powerful Images Translate Universal Values”

Moral realists believe that moral propositions express objective features of the world instead of individual sentiments. They find moral discourse meaningful and potentially objective. Intuitive as it may sound, moral realism is a controversial position in meta-ethics. The triangulation of exhibitions in the NUS Museum has been reflecting on the controversy. Stefen Chow and Huiyi Lin, part of the artist-duo known as Chow & Lin, for instance, advocate for moral realism in their photographic exhibition Homeless. The exhibition features satellite shots of geographical and urban landscapes, presenting vast expanses of impoverished areas alongside the mansions of the wealthy. In an interview with the curator Siddharta Perez, Chow & Lin opine that “powerful pictures translate universal values…(and) photographs have become a more common language”. Through their language, Chow & Lin express the severity of economic inequality across the globe. At first glance, Human Flow serves as a visual parallel to Homeless as the film is memorable for its large number of aerial shoots. But the documentary also shares the moral backdrop of the exhibition Homeless. Focusing on the scale and severity of the migration crisis, Ai Weiwei also conveys the shared responsibility on behalf of the audience. In a sense, Homeless and Human Flow both presume the existence of universal moral principles such as benevolence despite geographical and cultural biases.

Still, the cinematic medium of Human Flow allows the documentary to carry on the moral conversation further. The documentary allows its subjects to move, and in a sense, to flow collectively. The camera does not explicitly depict individual death or suffering; it purposely leaves a distance between itself and the subjects of documentation. Sometimes that distance is broken, at least temporarily, with Ai Weiwei exchanging passports with migrants arriving in Greece or comforting a Muslim woman crying in distress. That direct participation into the scene at first seems to deviate from the principle of documentary. That deviation can be intentional. It highlights the audience’s indifference and advocates for real actions instead of mere passive observation. That is, Ai Weiwei’s appearances in some of the scene act like a moral catalyst. Despite being a visual parallel to Homeless, the film feels more intimate as the camera footage helps the audience imagine relatable narratives happening before and after the documentary. That moral imagination unites the audience more than it divides.

If the camera helps one zoom in to relatable narratives in Human Flow by means of capturing the macro-scale at which movement and migration exists, it does the opposite in Last Train Home (归途列车) by director Lixin Fan: here, it guides audiences to zoom out to the bigger picture involving economic migrants in China by drawing focus to one particular story embedded within the wider milieu. In Last Train Home, the camera takes the audience to one migrant family, the Zhang family, with the teenage girl staying in the countryside and growing increasingly resentful of her parents’ absence in her life. The director painstakingly followed the Zhang family for three years before editing all camera footage to a documentary. In contrast to the New Year as a symbol of unity and togetherness, the Zhangs had been torn apart even though the parents did catch the train home. The documentary presents the social reality of a country where economic opportunism conflicts with traditional familial relations. The last train home is not a metaphor of reconciliation or reunion; it is a symbol of melancholy and helplessness.

Here, the audience’s gaze is funnelled through the lens towards two modes that are non-identical yet deeply intertwined in how they inform the story Fan places a spotlight on. From one angle, Fan’s directorial decision of honing in to personal stories outside mainstream media coverage exposes an easily veiled but embedded and emerging social crisis alongside the booming economy. While news outlets may focus on international refugees whose movements are necessitated by their lives being in immediate danger from threat of genocide or persecution, Last Train Home extends the moral imperative of action to domestic economic migrants whose oppression and poverty may not be as easily apparent, but their chronic struggle is equally painful.

From another angle, the camera’s focus becomes ostensibly intrusive to the extent that there is a clear sense of staged-ness, a performative aspect on behalf of the Zhangs who are too self-aware; Mrs Zhang who is on the brink of tears, realises the camera directly next to her lingering on her face and she turns away and holds herself back. This intrusion culminates in what could be the climax in a documentary-film in an instance of the fourth wall collapsing. Here, the daughter, quarrelling with her father, shouts at the camera: “You want to film the real me? This is the real me!”. Such discomfiting intimacy of the lens in relation to the subjects it gazes upon contrasts with Human Flow that pans over its subjects with broad, sweeping strokes, and yet the two documentaries together supplement the exhibition Homeless. While Human Flow serves as a visual parallel to Homeless, Last Train Home serves as a visual contrast. That visual difference does not necessarily translate to a moral difference. A documentary may prioritise either intimate or distant shots; the audience then have to imagine the other. The footage stimulates moral reflection on what has been done and what an interconnected world should look like in the future. Their strong moral imperative stems from its egalitarian underpinnings and commitment to moral realism.

“Who Are We to Dare Speak of Other People’s Stories”

Rather than advocating for moral realism that denotes a certain necessary distancing, Crossings seems more hesitant about making any moral judgements or prioritising certain voices over others. Instead, Crossings turns the notion on its head by problematising the idea of moral realism itself, by questioning whether moral discourse can be objective and meaningful to begin with. According to curator Sidd Perez, the exhibition explores how far one can speak on behalf of others. As different moral languages circulated and passed through the Archeology Library in different iterations of Crossings, the viewer was confronted with a large variety of opinions and orientations. The exhibition does not aim to settle, but only unsettle all establishments. The crossing point can be a geographical location, like how Singapore functions as an intermediary point of cultures and migrants. It also designates the metaphysics of selfhood, in the sense that the self is a crossing point of personal experiences and socio-political expectations. The exhibition problematises the conventional perception of a stable, predictable self until the point where one wonders whether one can still speak of oneself and others.

Flooding in the Time of Drought is conceptually analogous to the exhibition Crossings that explores connections and exchanges. Consisting of seemingly unrelated sub-stories that are both true in origin and fictionalised in presentation, the film specifically depicts how foreign migrants cope with a water crisis in an imaginary drought and flood-stricken Singapore. It does not make any claim about being a “Singaporean Story”, but rather is very much a “Story about Singapore”, reminding its audiences that Singapore is a crossing point of different languages and cultures in an interconnected and opportunist world. Existing just like water in a paradoxical state, human resource is both scarce yet abundant in Singapore. Some desperately want to come to the country, while others want to leave the crowded island-state. Far from being explicit, those sub-stories imply how a pending water crisis exposes a nation’s structural fragility and how another seemingly reticent, prosaic day in Singapore can be demanding and cruel.

In contrast to how climatic disasters are often portrayed in Hollywood blockbusters, the scenes in Flooding in the Time of Drought are often fragmented and shot in confined places mostly within public housing (otherwise known colloquially as HDBs), and in familiar rooms such as the living room, kitchen or common corridor. The shots are almost claustrophobic, with the content of these dialogues covering the region’s history, mythology and discriminations against gender, race and sexual orientation. The crossing point is never just about the point itself; it is always intertwined with stories and superimposed by socio-political contexts. The stationary, if not lifeless camera peeks into the everyday life of Singapore, and it wonders more than it fixes. It wonders through the existential dilemma of both an economic migrant and a nation at large. At times, it effortlessly blends reality with imagination, like how one of the characters, Sanjay’s girlfriend, joins him for a picnic on an HDB carpark roof after his death, with a formidable soundtrack featuring Chinese popular songs in the 1970s. The camera offers an imaginary space that merges flood and drought, love and death, as well as truth and myth.

How far can one impose moral judgements on those stories in Flooding in the Time of Drought? The stationary camera does not seem to be very enthusiastic about making such moral judgements. It simply narrates. In the second iteration of the exhibition Crossings, titled “you think it over slowly, slowly choose…”, photographs of the artist’s family are re-photographed, printed on tissue, re-arranged, and piled on the floor. Single-minded yet empathetic with all the stories it articulates, the exhibition rejects any pre-established narrative order or prescribed meaning. It debunks the strictures of chronology, possibly disorientating viewers, yet in its discordance, allows for one’s sense of self to arise and arrive, always in relation to the other voices in the exhibition space. In this light, the moral language surrounding Crossings and Flooding in the Time of Drought point towards an empathy and moral quietness that holds space for the voices of the subjects to emerge organically, without imposition or intrusion; for “who are we to dare speak of other people’s stories?”.

Are Reconciliations Still Possible?

The last film in the series, The Missing Picture (L’image Manquante), is the most open-ended. It concludes the series of film screenings but also sets the tone for further discussions. The documentary is framed in the form of personal recollection. Stemmed from the director, Rithy Panh’s own broken heart, the documentary remembers a childhood swamped with violence, injustice and impoverishment in the Khmer Rouge regime of Cambodia. The soul-baring production turns personal tragedy into something strangely beautiful. While the aerial shots blur one’s home from a physical distance, The Missing Picture blurs one’s home from a temporal distance. In this manner, the film adds a temporal dimension to the discussion of the exhibition Homeless.

The scenes of The Missing Picture blend historical footage with clay figurines, approximating a historical reality and at the same time avoiding it. In the slippages between reality and what is sustained in memory, Panh searches for and attempts to reconstruct the missing picture, offering the same processes of reckoning with, coming-to-terms with, and understanding to his audiences.. In a sense, the tensions between moral realism and subjectivism is elegantly summarised in The Missing Picture. It gently asserts a moral direction for audiences to take post-genocide, post-atrocities and yet, in a world where the effects of such devastation still lingers on its modern population; at the same time, it also does not take sides since there are no sides to be taken. Instead,it presents Panh’s story and waits for its audience to arrive and its conclusion.

It was only when watching the last film in the series when I realise that every documentary in Two Sides of the Same Lens is a missing picture, something that cannot be recovered or narrated in explicit details, something that can only be approximated by our pain, our collective conscience and our faith in humanity. It reminds me of the last exhibition in the triangulation: the prep-room project Of Place and A Paradox. As intriguing as it is demanding, the project gathers artists and viewers to determine their own projections and hopes for the region, creating art that subverts the media lens that often portrays Patani as politically unstable. Like The Missing Picture, Of Place and A Paradox does not present any conclusive remarks. It is a work in progress, a continuous development that seeks to potentially shape the reality of the world around it. Here, morality becomes de-centralised and shared. No one has the moral authority, yet everyone has a moral potential to act As such, audiences are simply asked to listen and make authentic choices. Instead of a moral imperative that clearly stimulates actions, both The Missing Picture and Of Place and A Paradox liberate and trust their audience.

As I reflected on the entire screening series, I realised that all the four directors featured in Two Sides of the Same Lens are migrants themselves. In some sense, these directors become part of the scenes they are filming, becoming partial actors in their films and projecting their aspirations, desires, selves into the narratives. . Although documentaries are primarily driven by visual realism, they also blend an unattainable historical reality with moral narratives . The latter, as these four documentaries demonstrate, is often prioritised over the former. Amidst the blending of reality and fiction, the camera serves as the tool that enables, complements, and disrupts the powerful exhortation each film makes for its audiences to reflect or to act. In presence, there is also absence. Where the audiences are guided towards what is shown by the camera, they are also similarly encouraged to imagine what is not shown, or cannot be shown. The five documentaries featured in Two Sides of the Same Lens beautifully bridge truths and fictions, documenting and staging, provocation and reconciliation.

Returning to the title Two Sides of the Same Lens, I noticed that the audiences and the subjects being documented are the individuals on the two sides of the same camera lens. As the proliferation of mass media proves to us, that thin lens can act as a powerful barrier that convinces the audience that they are not involved in the events being depicted and captured on the other side of the lens. The camera lens can also be ethically ambiguous at times, with the audience peeping into very personal lives and distant struggles. Some choose to respond to others’ sufferings; others remain indifferent. The lens can even be rather fragile or effectively non-existent at times, with the documentary directors participating in the scenes they shot or embracing the staged-ness of those scenes. What is also undeniable is that the lens is often part of a moral language: it can either symbolise symmetry, or resemblance, between the audience and the subjects being documented; it can also symbolise difference and inequality across distinct socio-political and economic situations. The interpretation of the lens is ultimately left to the audience to figure out, like to find a missing picture. These documentaries may deviate from visual realism, but they always dedicate their faith to humanity.

Many thanks to Mary Ann from the NUS Museum for editing the post.