This is the final essay I wrote for Film Philosophy at Amsterdam University College.

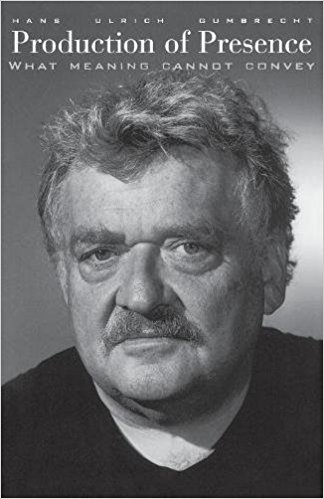

In Presence Achieved in Language, German-American literary theorist Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht is critical of the contemporary intellectual paradigm in the Humanities that primarily emphasises interpretation. Gumbrecht argues that only grasping the meaning of language, or art in general, is intellectually limiting as art can achieve more than just entail a well-circumscribed interpretation (318). In particular, Gumbrecht argues that art blurs the boundary between past and present, illusion and reality, and most importantly, absence and presence (317). As the central concept in Gumbrecht’s ontological argument, “presence” refers to an artwork’s tangible effects on people’s senses, emotions and bodies. It is through the presence achieved in art that people are fully engaged with aesthetic experiences when meaning-making is often delayed and subjective. In this essay, I contrast Gumbrecht’s insight with the cognitivist and Daniel Frampton’s phenomenological views on cinematic experiences. Borrowing scenes from Terrance Malik’s film The Tree of Life, I propose that cinematic expressions can create presence besides communicating stable, concrete meanings that mostly engage one’s mind. I side with Gumbrecht and argue that merely attributing or reconstructing the meaning of a film, cognitively or phenomenologically, limits the philosophising potential of the medium. After all, film intrinsically philosophises as a physical reality, or film-being.

Cognitivism represents a more analytic study of film. Valuing folk psychology and common sense (Frampton 150), cognitivist film theories put faith on normal human cognition and argue that film viewers passively receive information from the screen and rationally interpret it to understand a film’s philosophical insight and their own emotional responses to certain plots or characters. Cognitivism therefore regards cinematic experience as a constructivist mental activity that imagines a fictional film world and deciphers its meanings coherently (Frampton 156). Arguing for screen as the barrier, cognitivist film theorist Stanley Cavell believes that the screen necessarily separates the film and its audience who are forced to accept their absence in the film and maintain their indifference (23). The appeal of such cognitivist separation is its ontological parsimony: cognitivist film theorists deny the existence of the cinematic world; they regard the film world as fictional without the need to specify its ontological properties (Cavell 17). 1 On behalf of Gumbrecht, I argue that cognitivism is an intellectually limiting film theory that primarily strives to interpret a film. Ontological parsimony reflects the sense of “science-envy” 2 prevalent in the humanities where the subjects of study are often individual and nuanced. Cognitivist film theories ignore the nuanced human existence and idealise perception; they aggregate human experiences and overlook subjective and even uncontrollable cinematic experiences such as goose bumps and sweaty palms. It is too idealistic to assume that film viewers are rational all the time, or their common senses and cognitive faculties are always available to them during or after watching a film. Cognitivism is an oversimplified school of thought.

Similar to Gumbrecht, Frampton also finds rational, systematic cognitive interpretation an idealisation of cinematic experiences. He recognises that there is a sense of immediacy associated with cinematic experiences, and audience always experience the film before interpreting their experiences (Frampton 150). Experience itself, according Frampton, inherently carries meaning. People receive film’s subtle information, or the “basic units of their cinematic experiences”, while having embodied reactions as they experience the film, which results in immediate meaning-making (Frampton 156). Film is also thinking via its audio-visual designs and presentations, and film thinking even replaces audience thinking in movie theatre’s immersive environment. Dissatisfied with the cognitivist view on passive audience and dead screens, Frampton advocates for a more interactive or “organic” relationship between film and its audience: they interact in a film world and collaboratively form a unique mixture of thinking (161). Cinematic experiences are not cognitivist but phenomenological because Frampton acknowledges subjective, embodied first-person experiences and regard cinematic experiences as the exchange of consciousness. However, Frampton’s phenomenological view still focuses on the exchange of minds that results in meaning-making. In other words, a Framptonian film-goer still targets at the meaning of the film. Being critical of the cognitivist theories, Frampton nevertheless ends up treating cinematic experiences as a mental activity, however interactive it may be. On behalf of Gumbrecht, I argue that Frampton’s proposal is still incomplete because cinematic experiences as an exchange of thoughts alone cannot explain the normative and activating effects of cinematic experiences. Frampton’s phenomenological model cannot fully account for why audience cry during a film or, for instance, want to become a vegetarian or call their parents after watching a film. Gumbrecht would go beyond the exchange of minds and argue that film achieves presence like a tangible being so that audience interact with not just thoughts but also physical entities. Gumbrecht would argue that before any thoughts can be communicated in a movie theatre, film interacts with audience as a tangible being. In that sense, Gumbrecht’s theory, applied to cinematic experiences, address the ontology of cinematic experiences that often do not demand interpretation or simply cannot be interpreted. Frampton, on the other hand, is still ambiguous about the ontology of the cinematic world. Extending Frampton’s phenomenological view, Gumbrecht essentially looks beyond meaning-making and the exchange of minds while reaching a bold realist claim about the ontology of the cinematic world.

As a critique on analytic aesthetics and an extension of Frampton’s phenomenological argument, Gumbrecht’s aesthetic theory has been sometimes categorised as post-phenomenology.3 His argument critically examines Frampton’s concept of filmosophy and explores not just film-thinking, but film-being. Inspired by Martin Heidegger’s argument of language as “the house of Being”, Gumbrecht argues that art is first and foremost a physical reality, or Dasein, that helps people reconcile their past with present, their inner self with surrounding environment (317). He argues that what can be counted as present is not necessarily its locality or perceptivity, but its interaction with and tangible effects on audience senses, emotions and bodies. According to Gumbrecht, the relationship between film and its audience is never just dedicated to meaning-making but extends beyond meaning and integrates “spiritual and physical existence into the audience’s embodied self” (319). As a form of art, film-being is also a tangible reality by Gumbrecht’s criteria because it engages human body in its totality and exerts certain normative force or motivating thoughts on audience. For instance, not only can film engage the audience’s audio-visual sense, it sheds lights on its audience’s skin and keeps them silently attentive, which may not carry any concrete meanings. Gumbrecht’s emphasis on the actuality of presence achieved in cinema is not addressed in cognitivist or Frampton’s phenomenological film theories. Gumbrecht has a bolder claim than the above two schools of thought and as a result offers the most comprehensive account of cinematic experiences.

To illustrate Gumbrecht’s aesthetic theories applied to cinematic experiences, I now turn to three specific scenes from Malik’s film The Tree of Life, an experimental cinematic production that, in my opinion, constantly rejects interpretation but asks for a willingness to participate or simply be present with the film. For instance, in an extremely sensual moment, the teenager protagonist, Jack O’Brien touches a lingerie for the first time. There were no lines of communication in the scene or anyone else in the same room, but only a boy’s hesitant but eager touch of what was in his eyes the most alluring object. The window was open, and the afternoon breeze of summer sways the half-transparent silky curtain. A cognitivist film theorist would probably commend on the cinematography and how camera helps audience construct the understanding of adolescent sexual awakening, the most probable and stable meaning to be discerned from the scene. At the same time, Frampton may ask its audience to slow down and feel the image first, to feel the facial expressions of the boy and the nostalgic colour of the sunshine. Frampton would then attribute all the audio-visual information to the film’s thinking process and mostly likely deduce a meaning similar to the cognitivist inference. I argue that neither perspectives can fully account for the audience experiences. Audience may feel something that does not inherently carry meaning; for instance, they may want to close the window for the boy or recollect their own adolescent memories, sexual awakenings and first secret crushes. Such feelings may be extremely personal that audience may never share with anyone, but nevertheless the cinematic experiences of the Tree of Life trigger specific moods. Such moods carry no concrete meanings, but they successfully grab the audience attention to the scene and the action of the teenage protagonist. In fact, any meaning-making effort during that scene may disturb the audience’s cinematic experiences. The combined effect of the scene is very sensual and personal, especially if one watches the Tree of Life in an enclosed movie theatre. With such emotional and sincere interactions with the audience, Jake almost becomes an autonomous, actual person for a moment. For that fleeting moment, audience feel present with the boy and “forget” the fictionality of the cinematic narrative.

A second scene I want to focus on is the film’s idiosyncratic style, or in particular, its unexpected switch between the narrative and a cosmic documentary celebrating the birth of life and morality. Amid the mother’s grief over the death of her son, the film suddenly turns into a visually resplendent account of the universe. “Where are You?”, the mother softly wondered, “what are we to You?”. Most of the “documentary scene” is accompanied by a string soundtrack but not verbal communications. A cognitivist film theorist will be eager to look for coherence in the narrative and the hidden backdrop that connects different parts of the film. It may recognise that the film advocates for certain religious worship, as the events of the cosmos seem to be presented in a sequence that suggests the existence of a Being, or God, designing and overseeing the arrival of life and morality. Frampton’s phenomenological view may be more hesitant at first, but Frampton would ask the audience to experience the images as if the film is thinking. Frampton would perhaps be more detailed and nuanced in his formation of the same cognitivist thesis; he might also consider audience bodily responses and what meanings those reactions convey through film thinking to reinforce the cognitivist thesis. Still, neither view provides a satisfactory account for the cinematic experiences when watching the film. I suspect that few audience can grab the above message behind the sudden switch to a cosmic documentary. In fact, I doubt whether they can grab any concrete meaning, if there exists any, without reading any critical, if not overly interpretive reviews. The idiosyncratic style almost deliberately discourages thinking or any rational effort of interpretation. Instead, it asks for patience and attentiveness. It asks its audience to pause their concern for the characters for a while, be present with the film-being, and to feel a sense of awe and wonder about the origin of universe, life and morality. The audience may very likely fail to grasp any concrete meaning from the scene, even after watching the entire film, but they may be filled with sensations that no words can fully express. People may, for a short moment, even feel the urge change their religious perspectives if they are sufficient open to alternative perspectives. People who enjoy the “documentary” may feel compelled to recommend the film to their friends and family members; they may also search for the soundtrack online. Those effects carry no specific meanings but immediate feelings or actions. In those moments, film is not a fictional entity or a thinking agent, but an actual, physical being in order to exert such a tangible influence on its audience. Film moves, not just emotionally but also physically; its activating and inspiring effect can only be explained with Gumbrecht’s comprehensive treatment of aesthetic experiences.

The final scene on the beach is also noteworthy. Jack, then a grown-up and successful businessman, walked to a beach and found his deceased brother, an imaginary person of course, standing along the beach, perfect and clean. There were also many other people on the beach: the younger Jack and his younger parents. That powerful scene transcends life and death, past and present, dream and reality. There were again no lines of communication in the film, but characters all look cheerful, along with a rather gospel soundtrack. A cognitivist film theorist may find the ending unsatisfactory because it does not seem to end the narrative with a concrete message but confuses the audience even more. He may even find the ending arbitrary to some extent. Frampton, on the other hand, would pay more attention to the cinematic elements like the sunshine or the scene along the beach. He would challenge the audience to immerse themselves in the scene and image a meaning formed with the film, be it a reconciliation with past memories or a resolution to past mistakes. Frampton may infer from those mental actions to form the meaning of the scene. Gumbrecht would again move beyond meanings. It is firstly very difficult to tell whether the ending carries a meaning or a clear resolution for the entire narrative, but the scene evokes the need to pray among its audience regardless of their religious affiliations.4 As characters all look peaceful and grateful, audience may in a moment want to join them on the beach, or to touch the faces of those adorable children as if they are God’s grace. It may not be a logically satisfactory ending for the narrative, but it is an emotionally satisfactory ending for the audience’s cinematic experiences. All senses of awe, wonder and imagination are accumulated in that cinematic climax with Jack finding his young brother on the beach and his parents finding redemption. Audience, together with Jack, make peace with their present worries, past regrets and most importantly themselves. The audience may even feel the urge to pray for the dead and express their love to the living after watching the film; such behaviour is hard to be explained as rational choices or a result of purely mental activities. Rather, film is behaving like a Heideggerian Dasein and guiding its audience via spiritual interactions.

The implications of Gumbrecht’s ontological theory about art in general as a physical reality are thought-provoking: the theory questions not just the medium of doing philosophy but also the nature of philosophy. Firstly, essay-writing and film, or any art in general, seem to philosophise differently. While a philosophical essay presents structured arguments and engages its reader’s cognitive faculties, art evokes emotional, spiritual and bodily reactions. While it is certainly limiting to cognitively interpret a film as if it is an essay, it is also unfair to dismiss a film’s philosophising capability simply because it is not a well-structured argument. Film needs to be treated more seriously as a medium that philosophises in a distinctive way through the presence it creates. The presence achieved in film not just engages cognitive faculties of the audience, it also unsettles, liberates and inspires. It is when a film-being is recognised as a physical reality that cinematic experiences can be fully explored, and the film’s philosophising potential can be maximised. The second implication is more profound, if not radical. In the western intellectual tradition, the mind has often been prioritised as the essence of human while other parts of human existence are deemed peripheral. Philosophy, as a result, has always been treated as the exercise of the mind and cognition. But Gumbrecht’s aesthetic theory criticises that intellectual tradition and explores a fuller range of human experiences that involve the bodily, spiritual and interpersonal aspects of existence. Meaning, an essentially cognitive construct, now indeed seems intellectually limiting. Gumbrecht, embracing a fuller version of phenomenology than Frampton, implies that philosophy can be, or perhaps even should be non-cognitive, personal and metaphorical. With Gumbrecht’s perspective, film can be a rather promising philosophising agent. While an argumentative essay mostly engages the mind, film-being interacts with its audience and involves a larger range of human experiences, be it conscious or unconscious. All human faculties including but not limited to the cognitive faculty are involved in philosophising with the film-being. Philosophy is not just understood in a film, but felt, experienced and integrated into human existence. Through such genuine interactions with film-being, audience regard life as philosophy and philosophy as life.

To sum up, through cinematic experiences, audience surrender their cognitive faculties and engage in genuine interactions with the film-being. The pioneer of film studies Andre Bazin once says that photography is invented out of mankind’s obsession with realism (12). Cognitivist film theorists may read Bazin literally: the cinematic world resembles the real world as much as possible. Gumbrecht, on the other hand, would read Bazin phenomenologically: through film, audience interact what is the ultimately real, a physical reality, or the material presence achieved by cinematic expressions. Gumbrecht in the end provides a more comprehensible account of cinematic experiences. As another Heideggerian “house of Being”, film liberates audience from the constrain of space-time and functions as the ultimate philosophising agent.

Words Cited

Bazin, Andre, and Hugh Gray. What is Cinema? University of California Press, Berkeley, 1967.

Cavell, Stanley. The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1979.

Frampton, Daniel. filmosophy. Wallflower, London; New York, 2006.

Gumbrecht, Hans U. “Presence Achieved in Language (with Special Attention Given to the Presence of the Past).” History and Theory, vol. 45, no. 3, 2006, pp. 317-327.

Malik, Terrence (director). The Tree of Life. Brad Pitt, Sean Penn, Jessica Chastain (Main Casts). 2011